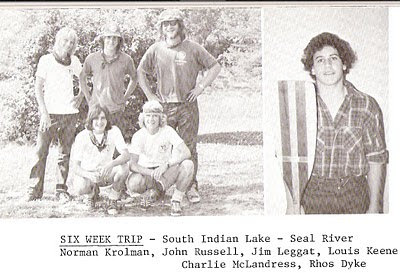

Alfred David (Davey) and Jim Stibbard (1958)

Alfred David (Davey)

Alfred David (Davey)

HOMESICKNESS: A condition that usually afflicts the young, but it can strike even the most life-seasoned among us when far from familiar faces and surroundings. Most likely everyone can recall that deep ache and the sense of isolation that comes with the longing to be back home. The comfort of loving arms is the surest cure. But until they are open once again, this malady can seem unbearable, even incurable. The following is a story based on my recollections of being a counsellor for young boys at a YMCA camp in the late 1950s. - Hal Studholme, Feb. 2008

It was the first day of sunshine after four days of miserable weather and it was a beauty. Lake of the Woods can be cold, windy and downright uncomfortable when it rains, but when it dawns clear and fresh with a blue sky that stretches into forever, there is no place like it short of heaven on a Sunday morning.

The island was brimming with the hustle and bustle that is the norm when you gather 140 boys together, all bent on cramming into two weeks the most fun and adventure humanly possible. All camp was happy, except for one small boy.

Wyatt leaned against the rear wall of the kitchen, chin sunk deep into his chest, his back pressed flat as if he were trying to merge with the faded white boards. His mud-spattered legs, one crossed over the other, were stuck out in front of his hips like skinny props. The once-white running shoes which he sported with such pride when he charged off the camp launch with a crowd of other boys were scuffed and stained. He didn’t wear socks. At camp nothing slowed a guy down more first thing in the morning or getting ready for the afternoon swim than socks. Nobody wore them.

Wyatt’s counsellor Grant stood beside him, leaning over, one hand on the boy’s trembling shoulder. Normally, just being in the presence of Grant would bring a smile to Wyatt’s face. The young boy idolized his counsellor. Grant seemed to be explaining something, but whatever it was it didn’t seem to help as Wyatt shook his head and then slowly slid down the wall to end sitting on the soggy ground. A bit more mud wouldn’t show on those shorts which had suffered mightily from the same rainy weather as the shoes. Only Wyatt’s T-shirt seemed to have managed, miraculously, to keep a few spots in its original sunny orange hue, but the typical round Happy Face emblazoned on it was obviously out of place right now.

Wyatt wrapped his arms tightly around his drawn up legs and dropped his forehead to rest on his dirty knees. He choked back a sob. He was a picture of defeat. Not knowing what else to offer in support, Grant slumped down beside his young friend. He too looked defeated.

Wyatt was small for eight, almost a head shorter than his cabin mates. Hunched there by the kitchen steps he looked even smaller. His size and the thick blond curls which fell almost to his shoulders often drew taunts of, “Hey, little girl,” from the older boys.

After the first day of camp and several of those remarks, Wyatt had begun to think his dad was right, maybe it was time to get him a brush-cut like all the other boys in his school class. But, as expected, Wyatt’s mom and especially his grandmother, were horrified. End of argument. Even then he could have weathered the taunts had it not been for the rain.

There were plenty of great things about camp. He really liked the other guys in his cabin and Wyatt had struck up a strong friendship with the boy on the top bunk over him. The first three days had been filled with so much activity that, at day’s end, they barely stayed awake to the end of taps. Grant often said, “Good night guys” to eight smiling, sleeping bodies. Then came the rains.

It’s one of the most challenging aspects of creating programs for a resident camp, filling multiple, consecutive rainy days with diversionary fun. There are just so many indoor activities one can organize before you have experienced too many craft projects, sing songs, skit nights and story fests. Even extraordinary efforts by the cooks to produce new versions of beans and wieners and morning porridge fell flat. Eventually the smiles of staff and counsellors take on that strained look of people getting to the end of their store of ideas and their patience.

For Wyatt, the fun wore thin by the third day. On the fourth the dam burst. After a night of nearly constant sobbing, he had begged his counsellor to call his parents. The homesick bug had hit full force. He wanted to go home.

At a boy’s camp, homesickness is something to be fought and defeated. Giving in to it doesn’t grow manly character, or such was the thinking in camp circles of the day.

A hard press of hyper-activity, beaming smiles, lots of laughter and constant buddy-buddy companionship from Grant and other counsellors and staff were the weapons of choice. All missed their mark. Wyatt’s sadness deepened and Grant determined it was time for the ultimate treatment. Slumped together in their mutual funk, neither Wyatt nor Grant seemed to notice the tempting aroma of fresh baked bread that wafted through the screened door of the kitchen as it swung open with a squeal of rusted hinges.

A tiny figure in a stained white coat and a crumpled cap that said, “Purity Flour” on its front stepped out. Davey, 80 years old and cook for more than 40, was a camp legend. The old man had been up since four o’clock preparing a breakfast of oatmeal for the nearly 200 hungry souls that inhabited the island camp in the summer.

Davey wearily sat down on the weathered steps and reached out a thin calloused hand to ruffle the boy’s tangled mop of hair. While cooking was his pride and joy, it was spending eight weeks with “my boys” that drew him back every year, despite declaring each fall that this would be his last summer at camp.

For a long while, no one said a word. Then, slowly, Wyatt’s arms loosened their tight wrap around his legs and he looked up and tilted his head towards the old cook.

As a junior camper, Wyatt sat at one of the front tables in the dining hall and he often caught Davey giving him and the other juniors a big wink and a smile from the kitchen pass-through where the food came out in steaming bowls and heaped-high plates. Davey and food were a camper’s best friends.

The bright July sun caught Wyatt’s small round face. His soft brown eyes were brimming and streaks from many tears glistened on his pale white cheeks. He lifted a grubby hand and scrubbed his face, then wiped his runny nose on his arm. Davey began to talk to Wyatt in a quiet measured tone.

Whatever wisdom and comfort the words held, they flowed over the boy and his counsellor and seemed to calm both. After a few minutes the hint of a smile flickered across the boy’s face and the thick curls shook as Wyatt nodded his head.

With a knowing chuckle the old man called something over his shoulder into the din of the kitchen and a few moments later the door opened and one of the kitchen boys, a broad grin on his sweat-streaked face, handed out three plates, each holding a large slice of what appeared to be blueberry pie. Huge scoops of ice cream crowned the offerings. Wyatt’s eyes widened and his smile broadened. Grant stifled a hoot of laughter. He had heard of, but never experienced, one of Davey’s “treatments”. Forks in hand, the cook, the boy and the counsellor dug into the delicacies with delight. Davey’s blueberry pies were as famous as he was to generations of campers and staff.

When you’ve been around boys at camp for more than 40 years, you get to know a cure or two for homesickness. The old cook watched as Wyatt and Grant walked across the playing field, arms around each other’s waists. For now, Davey’s remedy seemed to work once again......but tomorrow’s forecast called for showers.

Alfred David’s last summer at camp was 1961. He died that winter. His first summer was in 1920. His former job was in a factory assembling oil cans. In 1966 the chapel was dedicated in his memory.

.jpg)